During my visit at Grüne Woche 2020 back in February, the world’s biggest trade fair for food and agriculture, a short film presented by the Madagascan exhibitors about the impacts of climate change on the island country Madagascar had a big impact on me. It showed how already today, severe climate conditions take away natives’ means of survival, leaving home stock without food and drying bodies of water losing fish.

Climate change is causing more people to be displaced within their home countries every year. While migration and climate have always been connected throughout human history, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the leading UN body on climate science, has repeatedly pointed out that more people will be directly affected by the impacts of climate change, such as degradation of agricultural land, depletion of natural resources such as fresh water and disruption of ecosystems. In this context, the terms “climate migrant” and “environmental migrant” have emerged.

Migration in the context of climate change

According to the United Nations University’s Institute for Environment and Human Security, climate migrants “are people who leave their homes because of climate stressors”. Climate stressors range from heavy flooding, sea level rise, changing rainfall to severe heat waves, making people’s homes migration function as an adaptation strategy to climate change. Often, the people affected leave their rural livelihoods behind and move to cities in an ongoing trend towards urbanisation.

Looking at the meteorological impacts of climate change, we can differentiate between two drivers of migration. One the one hand, climate processes such as desertification and growing water scarcity, sea-level rise and salinization of agricultural land drive migration. On the other hand, migration is driven by climate events such as flooding and storms. However, non-climate drivers also play an important role, as climate change cannot be singled out as the sole driver of migration, which is often fuelled by other factors. This includes factors which contribute to the degree of vulnerability people experience, such as existing government policies, population growth and community resilience.

As the topic of climate migration is still a relatively new research field, little reliable data on the actual numbers of affected people is available. Some estimates, albeit highly contested, suggest that in 2018 alone, approximately 16 million people were displaced and forced to move from their homes due to climate change-induced extreme weather events such as flooding, drought-related fires and storms.

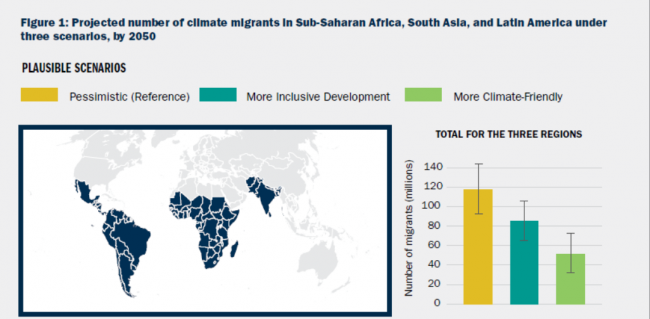

The IPCC predicts a global temperature rise by 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2040. If no climate action is taken, by 2050 internal climate migration could amount to 143 million people in three regions of the world alone, according to projections made by the World Bank (see Figure 1).

Projected number of climate migrants in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America under three scenarios, by 2050. Source: World Bank, Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration.

Northwest Africa is facing rising sea levels, drought, and desertification. These conditions will only add to the already substantial number of seasonal migrants and put added strain on the country of origin, as well as on destination countries and the routes migrants travel. The destabilizing effects of climate change should be of great concern.

The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration called on countries to make plans to prevent the need for climate-caused relocation and support those forced to relocate. However, these agreements are neither legally binding nor sufficiently developed to support climate migrants—particularly migrants from South Asia, Central America, Northwest Africa, and the Horn of Africa.

However, as Dina Ionesco, the head of the Migration, Environment and Climate Change Division at the UN International Organization for Migration (IOM), points out, our level of awareness and knowledge of the issue has significantly increased, enabling us to take informed action and effectively prepare for and respond to the ensuing developments in a changing climate.

Towards a global roadmap of action

A keystone agreement that makes clear climate migration is now accepted and recognised as a global challenge is the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (GCM). It was adopted by 164 countries in December 2018, who committed to cooperate on the governance of international migration. The document’s cooperative framework builds on 23 objectives, the second of which lays out the need to “minimize the adverse drivers and structural factors that compel people to leave their country of origin”.

Specifically, this means prioritising solutions that enable people to stay in their countries of origin and strategically adapt and build resilience to changing climatic and environmental conditions. Under the fifth objective, the GCM sets out to “enhance availability and flexibility of pathways for regular migration”, if adaptation in or return to the country of origin is not possible due to the intensity of climate change impacts.

It is clear that adaptation strategies form a key solution in the climate change-migration nexus. Essentially, it is about reducing vulnerability to climate change and increasing people’s resilience through appropriate governance strategies. However, the key objective should be to take preventive measures in the first place, focusing on and heavily investing in climate change mitigation strategies, as laid out in the Paris agreement.

Advancing urban mitigation and adaptation strategies to address climate change-induced displacement

Cities are a leading force in tackling global climate change and have an important role to play in addressing the climate change-migration nexus. Today, in our age of urbanisation, around 55% of the world’s population live in cities. According to UN projections, this number will increase to almost 68% by 2050, with 90% of urban growth expected to take place in Africa and Asia.

The economic and social development that takes places as more and more people are drawn into cities results in cities being responsible for about 75% of energy and resource consumption and energy-related greenhouse gas emissions. With the population numbers projected to live in urban areas, it becomes clear that the global climate crisis can only be tackled if sustainability becomes the focus of urban development and planning. To move towards a low-carbon and resilient future, urban mitigation and adaptation measures need to be implemented, including:

- Reducing greenhouse emissions by implementing sustainable transportation strategies and systems. Examples are carpooling, walking, biking, electrical and solar-powered cars, shuttles and buses. Large corporations like Google, Amazon and Facebook providing shuttles for their employees for remote locations (for example for headquarters in Mountain View and Sunnyvale, CA) to avoid having employees commute by single occupant car or other means of transportation. Another sector of greenhouse emission is decreased by adaptation of new government-level policies allowing use of refrigerants only with ozone depletion potential (ODP) of zero and global warming potential of 50(GWP) or at least banning CFC-based refrigerants, switching to wind and water-powered electrical stations etc.

- Sustainable agriculture and food production. multiple companies make it possible to grow food not only in cities but also in supermarkets. One of these companies is Infarm, which promotes urban vertical farming practices that allow growing nutritionally rich food with minimal waste and transportation – some of the biggest contributors to pollution and climate change. Many other ideas have been developed by individuals that want to change practices on how our society consumes food. So-called „farms of the future „designed to use no soil and 90% less water. With advanced technology and further development of biotechnology, matching essential flows like energy, water, nutrients and waste, the so-called “urban metabolism” can be determined and improved.

- Reuse and cascading of resources. The cascading approach to utilization of materials allow the reuse and recycling of products and raw materials and promotes energy use only when other options are starting to run out, expand the availability and use of high-quality secondary materials. Or more widely used approach called “3 Rs of Environment” – Reduce, Reuse and Recycle -the strategy being gradually implemented by many businesses and corporations across the world. For example, 70% of construction waste and 50% of the paper waste from households are on a target this year (Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC). One of the pioneers is The Cascading Materials Vision organisation.

- Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by adaptation of new government-level policies allowing use of refrigerants only with ozone depletion potential (ODP) of zero and global warming potential of 50(GWP) or at least banning CFC-based refrigerants.

The 2030 Agenda underlines the shared responsibility of all stakeholders: politics, business, science, civil society – and every individual.

With the 2030 Agenda adopted in 2015, the international community under the auspices of the United Nations committed itself to 17 global goals for a better future.United Nations have adopted 2030 Sustainable Development Goals Agenda (SDGs) focusing efforts on achieving the 17 different goals, pressing issues such as gender inequality, poverty, hunger, climate change, polluted drinking water , the droughts that perpetuate hunger crises and the rising tides that threaten coastal communities, and having access to good quality and sufficient supplies of food.

But what could it actually mean for a global population in the future? Most likely shortage of food supply, overpopulation, cities growing vertically and adjustment of public and private transportation. What do these developments imply for environmental and sustainability practices? Every year, it’s getting more challenging to grow food sustainably due to high demand and rapid consumption, clean water is becoming more deficit and most people are moving to the cities which will result in a lack of farming practices.

According to the United Nations, the world population is expected to increase from 7 billion to over 9.3 billion. 95% of urban growth will be in developing countries and climate migration will affect redistribution of the population, with d 3 billion people expected to live in urban settlements or mega-cities. 68% of the population will live in cities by 2050.

Often, such change causes a shift in the way we organize our society, including the provision of tools and systems serving a city or area, such as transportation, food, energy, and clean water and other fundamental needs. Most developed cities regarding prosperity and functionality is based on five indicators, or “dimensions”: productivity, infrastructure development, quality of life, equity and social inclusion and environmental sustainability.

Focus to achieve sustainable development, often referred to as Triple P: People, Planet and Profit. Within this Triple “P” approach, 24 different aspects to address sustainability in our living environment are framed. In this “Planet” aspects related to the technical aspects, or so-called “stocks” and “flows” in the local environment, like energy, space, water and waste. The ‘People’ aspects, as shown here, are related to liveability, like air or soil contamination, safety and quality-related aspects, such as available green and social inclusion. The “‘Profit”’ related aspects concern economic vitality and future values such as local employment, flexibility, and robustness. The hardest part is to coordinate different layers of government to develop a joint force with society – this would be the biggest challenge for the cities.

Furthermore, reuse and cascading of resources is easily implemented in urban areas; as the supply and demand of large quantities of waste resources is in close proximity. Sustainability and reducing contaminating emissions, so in vogue in recent years, is another example of how the increased population requires changes in city transport systems. Just 20 years ago, it was impossible to imagine that cars would be removed from city center or that private transport would be based on electric, shared and autonomous vehicles.

What are the solutions and sustainable practices to prevent complete industrialisation of farming and food production? Right now, multiple companies make it possible to grow food not only in cities but also in supermarkets. One of these companies is Infarm, which promotes urban vertical farming practices that allow growing nutritionally rich food with minimal waste and transportation – some of the biggest contributors to pollution and climate change. Many other ideas have been developed by individuals that want to change practices on how our society consumes food. So-called „farms of the future“ designed to use no soil and 90% less water. With advanced technology and further development of biotechnology, matching essential flows like energy, water, nutrients and waste, the so-called “urban metabolism” can be determined and improved. Otherwise, a combination of urban growth and poverty can put huge pressure on existing urban environments, creating unliveable environments.

These are concepts that are becoming a reality with an eye already on the next step. These are just a few examples that prove the incredible adaptation of cities to accept the great challenges that come with high population growth.

As much complementarity and synergy can be advanced in seeking multiple environmental benefits, in my opinion, the most important aspect of addressing environmental migration is changing human mindset and shifting perspective from a mentality of scarcity of natural resources and space to learning how to work together, and think what to do next to help the society, your local community and planet on a bigger scale. The question I ask myself daily is: how I can be of greatest service to the best possible future for humanity and the planet? Same applies to integration of immigrants into new, most likely better-developed and more technologically advanced society. Immigration policies to become more rigorous while the creation of new sustainable living models in developed cities will be necessary. By showing what is possible, such as creating voluntary policies and small-scale improvements of the way we treat food, waste and use energy can lead to changes in the formalised policies. I believe this is the only way we can transition from a win-lose system to a win-for-all system where we design our society to work for the common good — people and nature.

Sources/Further Reading:

UN News: https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/07/1043551

United Nations University: https://ehs.unu.edu/news/news/5-facts-on-climate-migrants.html

World Bank: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29461

Smart City Lab: https://www.smartcitylab.com/blog/urban-environment/smart-city-in-data-infographic/

IOM International Organization for Migration: https://www.iom.int/migration-and-climate-change?wptouch_preview_theme=enabled

Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration: https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/73/195

BMZ: https://www.bmz.de/en/issues/klimaschutz/migration-and-climate/index.html